Things You Didn’t Know About the Arizal

Last Friday, the fifth of Av, was the yahrzeit of the great Ari HaKadosh or Arizal, “The Holy Lion of Blessed Memory”, Rabbi Itzchak Luria (1534-1572). Few have had as monumental an impact on Judaism as the Arizal. Despite being an educator for only a couple of years, and passing away at the young age of 37 or 38, his teachings shaped the course of Jewish history for the next five centuries, until the present. Who was the Arizal, what did he reveal, and why was he so influential?

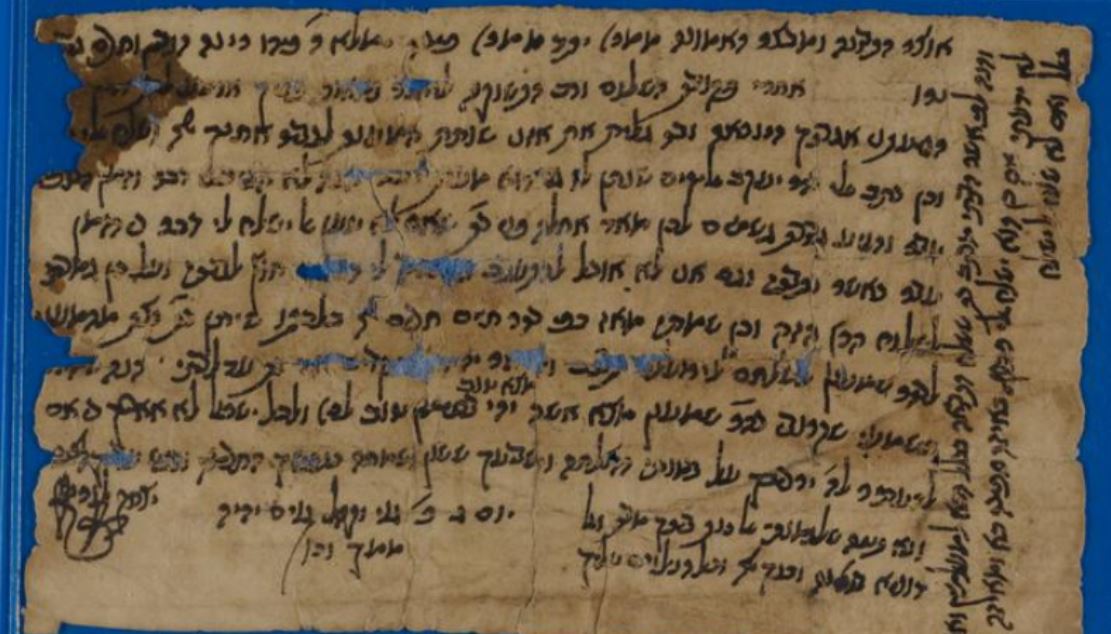

The Arizal was born in Jerusalem, the son of an Ashkenazi rabbi, Shlomo Luria, and his Sephardic wife. His father passed away when young Itzchak was only a boy, prompting his mother to rejoin her extended family in Egypt, where the Arizal was raised by his wealthy uncle, Mordechai Frances. The Arizal received the finest Jewish education, studying in the prestigious yeshiva of the Radbaz (Rabbi David ibn Zimra, c. 1479-1573), and also learning with Rabbi Betzalel Ashkenazi (c. 1520-1592). The Arizal married the daughter of Mordechai Frances when he was 15 years old, and continued learning full time. We know that once he was older, he did engage successfully in commerce. In fact, a couple of business contracts have been found in the Cairo Genizah bearing the Arizal’s own signature!

A business contract signed by the Arizal – his signature on the bottom left corner. (Credit: University of Cambridge Digital Library)

At the age of 22, he took up the study of Kabbalah and immersed himself deeply in the Zohar. His main disciple, Rabbi Chaim Vital, later wrote that the Arizal would sometimes spend an entire week meditating upon a single difficult Zohar passage (Sha’ar Ruach HaKodesh, Drush 1). Soon, the Arizal reclused himself to a cottage on the Nile River, living the life of an ascetic and spending his time in prayer, meditation, and Torah study. He would only come home on Shabbat to be with his family, and solely spoke the Holy Tongue instead of the vernacular Arabic and Ladino. (He did teach in Arabic when necessary, so that the students could understand him properly.)

Around age 35, the Arizal made aliyah with his family, returning to Jerusalem. It seems he wasn’t able to make a living there, and after several months moved north to Tzfat, already renowned as an epicentre of Jewish mysticism. Most likely, the Arizal joined the mystical circle of the great Ramak (Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, 1522-1570). According to one legend, the Arizal arrived in Tzfat on the day of the Ramak’s passing. The Ramak had told his disciples that whoever sees a mystical vision of a great flame upon his casket would be his successor. None of the disciples saw anything until the Arizal showed up and said something like: “Hey, do you guys see the flame above the casket?” This confirmed to the disciples that the Arizal should be their new leader.

Having said that, scholars and historians believe that the Arizal had arrived earlier in Tzfat, and did spend at least several months as the Ramak’s student. He showed his genius from the start, so when the Ramak passed away the Arizal quickly rose to the top of Tzfat Kabbalah. He only had a dozen or so disciples, most famous among them Rabbi Chaim Vital (1542-1620). The Arizal taught for only about two years before passing away very young. Despite this, his impact on Judaism is immeasurable. Among other things, the Arizal resurrected the old practice of Kabbalat Shabbat (his Tzfat colleague, Rabbi Shlomo haLevi Alkabetz, composed “Lecha Dodi”); popularized the custom of all-night study on Shavuot (and compiled the definitive tikkun text of study); and introduced the mystical Tu b’Shevat seder. His teachings gave rise to multiple Jewish movements in the centuries that followed and, more than anyone else, it was the Arizal that injected a “Geulah consciousness” into the Jewish world.

The Arizal’s Conduct & Worldview: Tzimtzum

The Arizal left nearly no writings of his own. It was his students who recorded his teachings, and the main such collection is referred to as Kitvei haAri. It was primarily composed by his disciple Rabbi Chaim Vital (1542-1620), though it did go through significant edits and changes in the decades that followed (more on this below). From these writings, we can learn a lot about how the Arizal conducted himself in his daily life.

We learn, for instance, that the Arizal never ate meat and dairy on the same day (Sha’ar haMitzvot, Mishpatim). We learn that he would regularly immerse in a mikveh, even in the cold of winter, and despite his mother’s warnings against it (ibid., Tetze). Indeed, the Arizal’s mikveh in Tzfat is still accessible today, and the ground waters are shockingly cold even in the summer! The Ari lived a very ascetic lifestyle, with frequent fasts. He was careful never to hurt any living thing, and not even kill so much as a fruit fly. Even if there was a bug that bothered him, he would abstain from shooing it away, for every living thing has a purpose for existing (Sha’ar HaGilgulim, Ch. 38; Sha’ar HaMitzvot, Noach).

He prayed and meditated a great deal, as we would expect. Still, he made sure to pay all of his employees daily. In fact, sometimes he would miss the proper time for Minchah because he was out arranging payment for his workers! (Sha’ar haMitzvot, Tetze) The Arizal did not write kame’ot, “amulets”, and was deeply opposed to that practice (Sha’ar HaMitzvot, Shemot). He said that no one knows how to do them properly, and they can actually do more harm than good.

The Arizal taught that one must divide their Torah study to cover all aspects of Pardes (the four levels of Torah study: simple, subtextual, metaphorical, mystical). His Torah study regimen is recorded in Sha’ar haMitzvot (on Va’etchanan) and is given as follows: He would first read verses from the weekly parasha, splitting it up so that he covers it all over the course of the week. He would repeat the whole parasha on Erev Shabbat. And he would always do it, as our Sages instructed, with shnayim mikra v’targum echad, reading the verse twice in the original language, and once in translation. He then read from Nevi’im, and then from Ketuvim, and then progressed to Mishnah, followed by Talmud, and finally Kabbalah. He studied Torah intensely, often to the point of breaking a sweat which, he taught, spiritually broke through the kelipot. This was at the heart of his philosophy:

The core of the Arizal’s mystical worldview began with the notion of tzimtzum, God’s “contraction” at the start of Creation. (Contrary to popular belief, the Arizal did not originate this concept or the term. It appears in much older texts, including the ancient Sefer haBahir and in the Zohar, too.) The Arizal taught that when God first created the cosmos, it was unable to contain His unfiltered light. There was a shevirat hakelim, a “Shattering of the Vessels”. The holy vessels broke into countless tiny nitzotzot, “sparks” of holiness. These sparks became trapped within spiritual “husks” and “shells”, kelipot. It is our mission to break through the shells and reveal the inner sparks of holiness, restoring them to their rightful place in the cosmos, to rebuild a perfect world. Every mitzvah accomplishes this, as does every berakhah, every prayer, and every act of kindness. There were many opportunities throughout history to complete this great cosmic tikkun, including in the Garden of Eden by Adam and Eve, and at Sinai by the Israelites. Each time, however, something went wrong. Piece by piece, throughout history, we are getting closer to completing all the rectifications. And only then will the Messianic Era begin.

Interestingly, the Arizal sometimes disagreed with, and disputed, the beliefs of earlier Kabbalists. A major case, for instance, is his denial of the notion of the “Cosmic Jubilee” and cyclical Shemittot where civilization restarts and repeats every 7000 years (Sha’ar Ma’amrei Rashbi, 46b). On the other hand, there were ideas that in previous generations were only vaguely alluded to that the Arizal dramatically expanded on. Perhaps the most notable one is reincarnation. One of the major sections in the Kitvei haAri is Sha’ar haGilgulim, “Gate of Reincarnations”, with long and detailed descriptions of how spiritual sparks move throughout the generations in the bodies of different people. It was thanks to the Arizal that reincarnation became widely accepted as a bona fide Jewish belief—and helped to explain so much about the Biblical characters that was previously hard to comprehend. (One of the Arizal’s students, Rabbi Israel Sarug, later moved to Italy and transmitted the Arizal’s teachings to Rabbi Menachem Azariah de Fano, 1548-1620, who composed Sefer Gilgulei Neshamot, another eye-opening textbook on Jewish reincarnation.)

The Arizal’s Passing: Shevirat haKelim

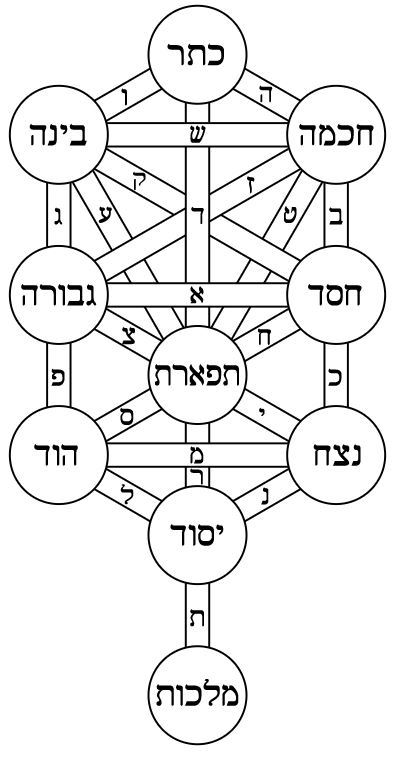

Rabbi Chaim Vital describes the “superpowers” of his teacher, which included communicating with departed souls, learning with the prophet-angel Eliyahu, reading people’s foreheads and physiognomy to “peer” into their minds and souls, and even understanding birds, trees, and the “speech of the inanimate” (Sha’ar Ruach HaKodesh, Derush 1). He could diagnose people’s issues by listening to their pulse and heartbeat, teaching that there are ten general types of pulse corresponding to the Ten Sefirot and the ten nikkudot vowel sounds of Hebrew. He could sense where various tzadikim, Biblical, and Talmudic figures were buried, and pointed out their resting places in Israel. (Sha’ar haGilgulim, Ch. 37. Bizarrely, he even points out here what is apparently the real grave of “Yeshu haNotzri”, just north of Tzfat!)

The Arizal was privy to secret knowledge from Heaven—but he was not always at liberty to reveal that knowledge to his students. Tragically, he explained the death of his young son to be because he revealed something he wasn’t supposed to (Sha’ar haKavanot, Inyan Chag haPesach, Derush 12). This was the deeper secret behind the Zohar’s mysterious description of a pregnant deer that gets bitten by a snake (II, 52b). The bite is necessary in order to allow the deer to give birth. In simple terms, the whole thing is a metaphor for the necessity of evil and the role of the “Serpent” in bringing about the Final Redemption. (For more on this, see ‘The Dragon, The Snake, and the Messiah’.)

Similarly, his untimely passing came because, it seems, his disciples were not friendly with each other and were not worthy of his teachings (Sha’ar haGilgulim, Ch. 39). On his deathbed, only his student Rabbi Itzchak HaKohen was by his side, and reported that the Arizal said: “Had even one of you been a tzadik gamur, I would not be passing away before my time…” Apparently, he then said that his disciples should stop learning, teaching, or spreading what he had taught them, since they did not properly understand it, and it would only lead to heresy! Moments later, he opened his mouth and his soul left him. His death is described as being by a divine “kiss”.

Despite his warning, his students did indeed continue to teach the Arizal’s lessons to others. This led to an unfortunate dispute. Rabbi Chaim Vital argued that he alone properly understood the Arizal, and only he should be allowed to disseminate his teachings. He went so far as to claim (in Sefer haHezyonot) that the Arizal came down into this world only to teach him and no one else! Understandably, the other disciples didn’t agree. Some believed that Rabbi Yosef ibn Tabul was the wiser one, and that he should take the lead. Others, that it should be the elder Rabbi Yosef ben Yakov Arzin. Another prominent figure was Rabbi Israel Sarug, who spread the Arizal’s teachings to Europe as mentioned above. Yet, he is totally absent from Rabbi Chaim Vital’s account of the disciples (in Chapter 39 of Sha’ar HaGilgulim).* Some say it is because he was not part of the Arizal’s inner circle, or that he did not live in Tzfat at all, and knew the Arizal earlier when they were both in Egypt (See Gershom Scholem’s Kabbalah, pg. 426). It’s possible that Vital really did not know Sarug, or that he deliberately excluded Sarug from the list. Vital also fails to mention Israel ben Moses Najara (c. 1555-1625), another key Tzfat Kabbalist and contemporary of the Arizal who later became chief rabbi of Gaza. A separate work called Shivhei Chaim Vital suggests the two did not get along, which might explain Najara’s omission from Vital’s work.

So, unfortunately, there are different versions of what the Arizal truly believed and taught. Although over time Rabbi Chaim Vital’s texts became authoritative, even he often admits in his writings that he wasn’t sure if he understood something correctly, or if he remembered it right, and sometimes he admits he doesn’t understand it at all, or that he only heard it from someone else. More problematic still, Vital did not allow these writings to be spread until after he died. Later, his son Rabbi Shmuel Vital (1598-1677) made further edits and added his own comments. These were modified even more by Rabbi Meir Poppers (c. 1624-1662), and it was the Poppers’ edition that was spread widely across Europe. So, we have no good way of knowing if everything in the current Kitvei haAri is authentic or not. And thus, studying the Arizal is not simple at all. One must use multiple sources and synthesize information from different domains. If something is mentioned only once, obscurely or surprisingly, it may well be suspect.** And there are often contradictions that have to be worked out. Ironically, the teachings of the Arizal have undergone a “shattering of the vessels”, and need tikkun.

The Arizal’s Vision: Tikkun and Geulah

More than anything else, the Arizal wished to usher in the Final Redemption. Everything he taught and did was in order to complete the necessary rectifications and bring Mashiach. In fact, he believed the coming of Mashiach was imminent. At the very end of Sha’ar haPesukim, the Arizal made a calculation of when the Final Redemption would begin, based on Daniel 12:7 which says “Praiseworthy is the one who waits and reaches one thousand three hundred and thirty-five days.” The Ari taught that this means 335 years into the sixth millennium, ie. 5335 AM, or 1575 CE. Now, he does not say Mashiach would come in that year, but that this was the year from which henceforth Mashiach could come. Sadly, he passed away just three years earlier, in 1572, around age 37. The age of his death is not coincidental:

We know that Isaac, son of Abraham, was taken to the Akedah when he was 37 years old. The Arizal explained that Isaac was a reincarnation of Abel. In fact, he points out that the gematria of “Abel” (הבל) is 37, secretly alluding to his binding in his future life as Isaac (Sha’ar HaPesukim on Lech Lecha and Vayera). Another allusion is in Abraham’s reply to Isaac’s question (Genesis 22:8) with the words haseh l’olah beni (השה לעלה בני) where the initials rearrange to spell “Abel”. Isaac was a rectification for Abel, who then returned again in Moses, the First Redeemer. Of course, the Arizal was himself an “Isaac”, and according to Rabbi Chaim Vital, described himself as the “Mashiach ben Yosef” of the generation. (Indeed, he revealed a great deal about Mashiach ben Yosef, and instituted a kavanah within the Amidah that Mashiach ben Yosef should not die.) It is therefore quite fitting that the Arizal passed away around age 37, like a modern-day Isaac at the Akedah.

The Ari’s teachings were deeply messianic, and scholars argue that they led directly to the rise of the false messiah Shabbatai Tzvi (1626-1676) in the following generation. Recall that Tzvi had little support until he met Rabbi Nathan of Gaza (1643-1680, likely a successor of the Arizal’s disciple Moses Najara, who taught in Gaza). Shabbateanism was based on the teachings of the Arizal, though they were twisted into a false direction. (Remember the Arizal’s warning on his deathbed that it would lead to heresy?) Hasidism later emerged to steer back these ideas into a kosher domain. Legend has it that the Baal Shem Tov (Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, 1698-1760, founder of Hasidism) “went down to hell” to wrestle with Shabbatai Tzvi and extricate whatever good sparks were there. One of the reasons Hasidism was originally opposed by the rabbinic authorities is because of a suspicion that it had Shabbatean connections.

Nonetheless, Hasidism serves as only one of three or four major streams of Lurianic Kabbalah, the others being the school of the Ramchal (Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto, 1707-1746) and the school of the Rashash (Rabbi Shalom Sharabi, 1720-1777). While some include it alongside the school of the Ramchal, others say the “anti-Hasidic” mystical school of the Vilna Gaon (1720-1797) is a separate stream. Altogether, that makes “four rivers out of Eden” (Genesis 2:10). These four evolving branches of the Arizal’s Kabbalah had immense impact on the course of Jewish history. All worked tirelessly towards bringing Geulah, and all sent emissaries—if not entire communities—to re-establish a vibrant Jewish presence in the Holy Land. The Rashash was born in Yemen and moved to Jerusalem where he became a rosh yeshiva. The Ramchal made aliyah and passed away in Acco. Both the Vilna Gaon and Baal Shem Tov attempted aliyah but were thwarted, instead inspiring hundreds of their disciples to make the journey to Israel (as explored previously here). This ultimately led to the formation of the State of Israel, and the current reality in which we find ourselves.

And so, the Arizal’s vision of bringing about the Final Redemption appears to be close to realization. I believe it isn’t coincidental that his yahrzeit is always right before Tisha b’Av, and right around Shabbat Chazon, when we read Isaiah’s vision of the End of Days and when, the mystics say, each Jew is given a “vision” of the Third Temple. The Arizal, too, had an intense vision of the End, and of the Final Redemption, and his teachings, more than anyone else’s, put the notion of Mashiach and the Geulah in the minds of the Jew. Related to this is one of his most inspiring teachings:

We generally speak of a yeridat hadorot, a “decline in the generations”, with today’s people not nearly as great as those of the past. However, the Arizal said that the kelipot at the End of Days are the strongest ever, the wicked Sitra Achra is out in full force, meaning it is far more difficult to be righteous in our generation than ever before. Thus, a small mitzvah today is equivalent to a huge mitzvah in generations past, and a tzadik today is actually greater than a tzadik in the past (Sha’ar haGilgulim, Ch. 38). We learn from this that even the tiniest mitzvah we do today reverberates endlessly with immeasurable positive consequences, and even the smallest good deed is a giant leap towards Redemption. May we merit to see it realized soon!

‘Going Up To The Third Temple’ by Ofer Yom Tov

*The names of the rabbis that Chaim Vital mentions: Yonatan Sagis, Yosef ben Yakov Arzin, Itzchak Kohen, Yosef ibn Tabul, Yehuda Mish’an, Gedaliah Levi, Shabbatai Menashe, Shmuel Uzida, Abraham Gabriel, Eliya Falcon. He parallels these figures to various aspects of the Sefirot.

**One example is the custom of kapparot. It appears just a single time, briefly, in Sha’ar haKavanot. It is hard to believe that the same Arizal who was so careful not to even shoo away a fly would allow a chicken to be swung around his head and then get slaughtered. Keep in mind that the Arizal’s contemporary in Tzfat, the great Rabbi Yosef Karo (1488-1575), a major Kabbalist in his own right, described kapparot as a minhag shtut, a “foolish custom”.

https://www.mayimachronim.com/things-you-didnt-know-about-the-arizal/

No comments:

Post a Comment