Ten Divine Songs

In this week’s parasha, Beshalach, the Israelites safely traverse the Red Sea and erupt in joyous song. This song, Shirat haYam, the “Song of the Sea”, is so important that it was included in our daily prayers. The Zohar (II, 131a) describes it as a song of redemption, and one that causes Israel to be “crowned” when we sing it, which is why it is the very climax of Pesukei d’Zimra, right before going into the Shema and Amidah at the height of our prayers. The Zohar says one who sings Shirat haYam with full kavanah will merit to see the coming of Mashiach. At the same time, Midrash Shir haShirim Zuta lists it among history’s ten special divine songs. What are these ten unique songs and how do they parallel Creation and the Ten Sefirot?

The first divine song is referred to as the “Song of Adam”. This is identified in other sources as Psalm 92, Mizmor Shir l’Yom haShabbat. The Zohar (II, 135a) explains that Adam wrote it in gratitude because Shabbat brought him peace and comfort following his expulsion from Eden. The song itself highlights the great significance of music, and how wonderful it is to praise God “through a ten-stringed instrument, and a harp, and a lyre”.

The second song is the most mysterious on the list, called the “Song of Abraham”. At first glance, there is nothing in Tanakh that indicates Abraham wrote a song. However, there are brief allusions to such a song in the Midrash, including in Beresheet Rabbah 43:9. We are given more information about it in an ancient apocryphal work called The Apocalypse of Abraham. The original Hebrew text has been lost, but an Old Slavonic translation does exist to this day. Much of the content of the first part of the text overlaps with what the Midrash says about Abraham, starting with his early years working in his father Terach’s idol shop. In the second part of the text, Abraham is led to Mount Sinai (Horev) by the angel Yehoel (usually identified as Metatron), and there confronts the fallen angel Azazel.

It is in the final part of the Apocalypse where we are told of Abraham’s Song. Abraham ascends to Heaven and witnesses the Merkavah, much like the opening vision in the Book of Ezekiel. Abraham is then given a vision of the End of Days and the coming of Mashiach. Then Abraham sings a song to God, as taught to him by Yehoel (Chapter 17). In a detailed scholarly analysis of the Song of Abraham, Steven Weitzman cites other sources suggesting the song was composed following Abraham’s miraculous escape from the fiery furnace of Ur, or upon his victory in the “War of the Kings” (Genesis 14). Whatever the case, we don’t know the exact content or original lyrics of Abraham’s Song.

The third song is this week’s Shirat haYam, and it is followed by the “Song of the Well” which was similarly chanted by all of Israel in the Exodus generation, but later in the Wilderness after miraculously receiving water (Numbers 21:17-20). Just like the Song of the Sea, the Song of the Well also begins with the words az yashir. Much has been said about the strange future tense of these introductory words, as if Israel will sing these words. It is commonly taught that these songs secretly allude to the End of Days, when all of Israel will once more be united and witness miraculous events just like in the Exodus generation, and again sing in national unity to God.

The rest of the ten divine songs are individual compositions: The fifth is the “Song of Moses”, Ha’azinu, considered by many to be the Torah’s most important parasha. The sixth is the “Song of Joshua”, which is not explicitly mentioned in Tanakh but is based on Joshua 10:12-13. This is when Joshua miraculously caused the sun to stop in its tracks so that the day would be prolonged for the Israelites to emerge victorious in battle. Joshua sang: “Stand still, o sun, at Gibeon; o moon, in the Valley of Ayalon!” The battle was miraculous for many more reasons, including that God sent down a torrent of stones and hail from the sky, “and more perished from the hailstones than were killed by the Israelite swords.” (10:11)

The seventh song is the well-known Song of Deborah (Judges 5), which is in the Haftarah for this week’s parasha. The eighth song is the Song of David (II Samuel 22), when “he was saved from all of his enemies, and from Saul”. This is the Haftarah for parashat Ha’azinu, and the same song is found in Psalm 18. In the Samuel version, the final verse begins migdol yeshuot malko, “A Tower of Salvations to His king, dealing graciously with His anointed, with David and his offspring forever.” In the Psalms version, it begins magdil yeshuot malko, “He magnifies the salvations of His king, dealing graciously with His anointed, with David and his offspring forever.” This verse is, of course, found in the conclusion to birkat hamazon, with the latter magdil recited in the daily version and the former migdol on Shabbat and holidays. The mysterious switch between magdil and migdol has puzzled many (for a detailed analysis, see Rabbi Dr. Raymond Apple’s essay on it here). One possibility is that during the week when we are active and productive, we fittingly use the active verb magdil, whereas on Shabbat when we are resting and delighting in God’s “spiritual sanctuary”—a Tower of Salvation—we use the noun migdol.

The ninth song is the “Song of Solomon”, ie. Shir haShirim, the “Song of Songs”, while the tenth is the Song of Mashiach, the “Song for the World to Come”, as it says in Isaiah 42:10 that in the future we will “sing a new song to God”. The passage in Midrash Zuta concludes by saying that Shir haShirim, the ninth song, is in fact the greatest on the list. It is worth recalling that some of our Sages were uncomfortable with its explicit lyrics, and suggested banning it or relegating it to the apocrypha, but Rabbi Akiva came to its defence. He declared that no one ever doubted the sanctity of the Song of Songs, and while all of Tanakh is holy, the Song of Songs is the “Holy of Holies”! (Yadayim 3:5)

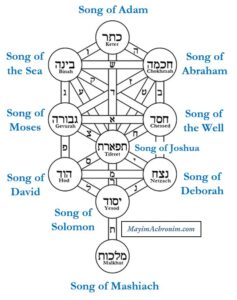

One can easily see how the above ten songs neatly correspond to the Ten Sefirot, in perfect chronological order. The first song to be revealed, the Song of Adam, is the first Sefirah of Keter, the initial Divine Will (and corresponding to the highest world of Adam Kadmon). It is all about Shabbat, “last in Creation, but first in thought” as we say in Lecha Dodi. Then comes the Song of Abraham, our first forefather, corresponding to Chokhmah, or Abba, the “father” Sefirah. Abraham was the first true chakham, the first to go out and teach God’s Wisdom to others. Next is the Song of the Sea, corresponding to the motherly Binah or Ima, and appropriately this is the song described as being prolonged by the ladies, led by Miriam. Binah is often compared to the womb, just as crossing the Sea was symbolically for Israel like the birthing waters of a new nation.

One can easily see how the above ten songs neatly correspond to the Ten Sefirot, in perfect chronological order. The first song to be revealed, the Song of Adam, is the first Sefirah of Keter, the initial Divine Will (and corresponding to the highest world of Adam Kadmon). It is all about Shabbat, “last in Creation, but first in thought” as we say in Lecha Dodi. Then comes the Song of Abraham, our first forefather, corresponding to Chokhmah, or Abba, the “father” Sefirah. Abraham was the first true chakham, the first to go out and teach God’s Wisdom to others. Next is the Song of the Sea, corresponding to the motherly Binah or Ima, and appropriately this is the song described as being prolonged by the ladies, led by Miriam. Binah is often compared to the womb, just as crossing the Sea was symbolically for Israel like the birthing waters of a new nation.

The Song of the Well, of course, corresponds to Chessed, always associated with life-giving water. The harsh Song of Moses is fitting for Gevurah or Din, God’s severity and judgement. The Song of Joshua—stopping the sun to allow for the conquest of the Holy Land—is for Tiferet, always associated with the sun, and with the Land of Israel. Deborah’s Song about another great military victory, with the Eternal One coming to save Israel from oppression, is Netzach. David’s glorious song of gratitude is Hod, and Solomon’s intimate Shir haShirim obviously parallels Yesod, just as the Song of Mashiach obviously ties to Malkhut.

Ten Songs of Israel

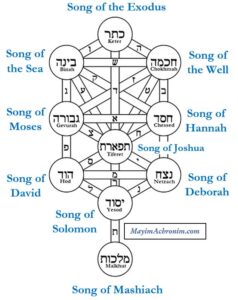

The above list of ten songs should not be confused with a very similar Midrash about the ten songs of Israel (see Tanchuma on Beshalach, 10). These are songs specific to the people of Israel, starting with the song that the Israelites sang on the night of the Exodus itself, based on Isaiah 30:29 which states “You shall have a song as in the night when a holiday is sanctified…” The Israelites then sang at the Sea, and at the Well, rounding out the first three of the Songs of Israel. These are followed by individual compositions: the Song of Moses, the Song of Joshua, the Song of Deborah, and the Song of David, all the same as the songs given in the previous list.

The eighth song is another work of David, but “for the dedication of the House”, Psalm 30, which David wrote for his son’s forthcoming inauguration of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. It seems some versions of the Midrash replace this one with the Song of Hannah (I Samuel 2). Hannah’s song is also of monumental significance, and our Sages point out that we learn how to pray from her example (Berakhot 31a). The ninth song is Shir haShirim, and the tenth the Song of Mashiach, or the Song of the Future, here based on Psalm 98:1, “Sing to Hashem a new song, for He has worked wonders…”

This list of Ten Songs of Israel parallels the Sefirot just as well as the previous list: the first three were sung nationally by all of Israel, and correspond to the higher three Mochin. The remaining seven were composed and sung by individuals, corresponding to the lower seven Middot. (The above diagram remains nearly the same, except that the Song of the Well—also representing the wellsprings of Wisdom—moves up to Chokhmahto make way for Hannah’s Song, describing God’s everlasting Chessed. And the first Song of Adam is replaced by Israel’s first, the Song of the Exodus).

This list of Ten Songs of Israel parallels the Sefirot just as well as the previous list: the first three were sung nationally by all of Israel, and correspond to the higher three Mochin. The remaining seven were composed and sung by individuals, corresponding to the lower seven Middot. (The above diagram remains nearly the same, except that the Song of the Well—also representing the wellsprings of Wisdom—moves up to Chokhmahto make way for Hannah’s Song, describing God’s everlasting Chessed. And the first Song of Adam is replaced by Israel’s first, the Song of the Exodus).

There is one more set of ten songs that needs to be mentioned. The Talmud (Pesachim 117a) notes that King David incorporated ten types of song in his Psalms: nitzuach, niggun, maskil, mizmor, shir, ashrei, tehilla, tefilla, hoda’a, and halleluya. We are then reminded of the great power of music, so much so that it can bring down the Shekhinah to rest upon a person, as it says of the prophet Elisha who specifically asked for a musician to come play for him because “As the musician played, God’s Hand came upon him.” (II Kings 3:15) That explains why many of our prayers are chanted and sung (as is the Torah itself), and why the preparatory stage of prayer before the Shema and Amidah is the musical Pesukei d’Zimra.

Similarly, the Zohar says that there are ten types of music, all emanating from the Ten Sefirot, and all connected to God’s Name. In fact, God’s Ineffable Name of four letters is itself a song that is “singled, doubled, tripled, quadrupled” (Tikkunei Zohar 27b). This perplexing statement has led to much speculation on its meaning, along with its identification as the “Song of Redemption”, or the “Song of Mashiach”, likely the same one as the “Song of the Future” and “Song of the World to Come” listed above. (I suggested one intriguing possibility for what it might be in the class on the ‘Kabbalah of Music’.) No one quite knows for sure what it means, or what it will sound like, but let us pray (and sing!) that we get to hear it soon.

Tu b’Shevat Learning Resources:

Secrets of Tu b’Shevat (Video)

Origins and Secrets of the Tu b’Shevat Seder

Where Did Tree-Planting on Tu b’Shevat Come From?

No comments:

Post a Comment