One of the highlights of this week’s parasha, Ki Tavo, is the instruction for the Twelve Tribes of Israel to split up on two opposing mountains—Gerizim and Eival—to hear a series of curses and blessings. Six of the tribes (Shimon, Levi, Yehudah, Issachar, Yosef, and Binyamin) were on Mount Gerizim, the “mountain of blessing”, and the remaining six (Reuven, Gad, Asher, Zevulun, Dan, and Naphtali) on Mount Eival, the “mountain of curse”. The tribes would later cross the Jordan River and settle across the Holy Land in their allotted territories—with the exception of Reuven, Gad, and half of Menashe, who stayed on the east side of the Jordan. One of the highlights of this week’s parasha, Ki Tavo, is the instruction for the Twelve Tribes of Israel to split up on two opposing mountains—Gerizim and Eival—to hear a series of curses and blessings. Six of the tribes (Shimon, Levi, Yehudah, Issachar, Yosef, and Binyamin) were on Mount Gerizim, the “mountain of blessing”, and the remaining six (Reuven, Gad, Asher, Zevulun, Dan, and Naphtali) on Mount Eival, the “mountain of curse”. The tribes would later cross the Jordan River and settle across the Holy Land in their allotted territories—with the exception of Reuven, Gad, and half of Menashe, who stayed on the east side of the Jordan.

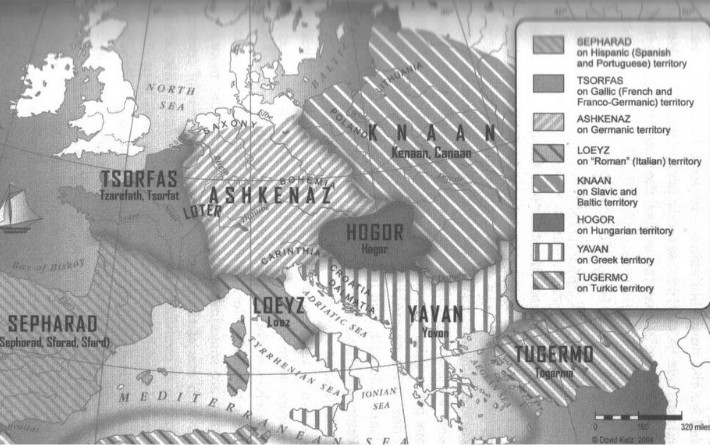

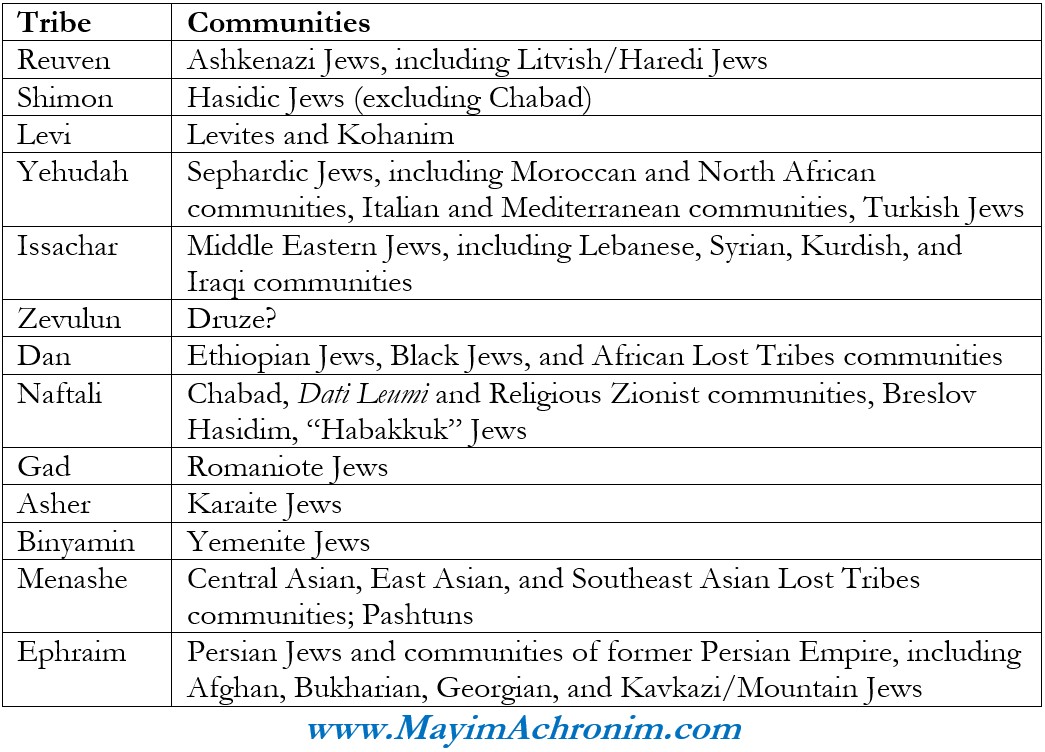

Centuries later, the tribes split up into two kingdoms: the northern “Kingdom of Israel” or “Kingdom of Ephraim” with ten of the tribes (or more accurately, eleven), and the southern “Kingdom of Judah” that was dominated by the tribe of Yehudah (and its Davidic kings) but also contained a sizeable portion of Binyamin and Shimon. After falling to the Assyrians and Babylonians, the tribal boundaries were erased, and soon tribal affiliations and identities were lost, too. Everyone coalesced into the dominant tribe of Yehudah, and so everyone became a Yehudi. Even Mordechai, who came from the tribe of Benjamin, is identified as a Yehudi in the Purim story. So, what will happen in the forthcoming Messianic Age when all of Israel will return to their Promised Land and presumably re-establish the ancient tribal borders? How will we see the “return” of all the tribes, when there are no clear tribal affiliations anymore? One possibility is that we actually won’t have tribal borders again, a case one can make based on Ezekiel 37 where God describes fusing together the branches of Yosef and Yehudah and making them one branch. Hashem declares: “I am going to take the children of Israel from among the nations they have gone to, and gather them from every quarter, and bring them to their own land. I will make them a single nation in the land, on the hills of Israel, and one king shall be king of them all. Never again shall they be two nations, and never again shall they be divided into two kingdoms.” (v. 21-22) The implication is that Israel will be a singular nation, with no internal divisions or boundaries, ruled by one king. Another intriguing possibility is to apply the ancient tribal divisions to the various “tribes” within the house of Israel today. We might be able to associate each of the tribes with the modern-day communities that we find within the Jewish people. If we explore the history, culture, and symbolism of the various groups among us today, we find striking similarities to the ancient tribes. What I would like to suggest in the following is a modern-day recreation of the Twelve Tribes of Israel—not genealogical or biological, but spiritual and symbolic. This would be similar to the way we refer to other peoples of the world: For example, we refer to all Christians as being part of “Edom”, even though the vast majority of them are not literal descendants of Esau. We refer to all Muslims as “Ishmael”, even though the vast majority of them are not direct descendants of Ishmael, and many are not even Arab at all, including major Muslim communities in Iran, Pakistan, and Indonesia (the world’s most populous Muslim nation). We find Amalek manifest in different peoples of the world who seek the destruction of Israel, even though they are not direct descendants of the ancient Amalek himself. We recognize that the physical aspect is secondary to the spiritual anyway, and entities of times past continue to exist today even without a clear genealogical or biological link. The same can be said for the Twelve Tribes. So, who might the Twelve Tribes be today? [Warning: what follows is admittedly speculative, and mostly based on symbolic meaning. We live in a generation where identity is a very sensitive topic, so I hope no one is offended or feels “miscategorized”!] Levi, Yehudah, and Binyamin The first and easiest tribe to identify today is the tribe of Levi, which has preserved its lineage for the most part. Levites and Kohanim generally still know who they are, based on what their fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers told them, generation after generation. (Although it is true that they can’t necessarily prove it empirically.) Yehudah might seem easy to identify, since we are all Yehudim, but we must remember that “Yehudi” became a generic term for everyone. Even Levites and Kohanim identify as Yehudim today, although they technically aren’t! So, who are the actual tribal Yehudim? We have a major clue from Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo Itzchaki, 1040-1105). On Ovadiah 1:20, which speaks of the exile of the tribes of Israel and of the Judeans of Jerusalem, Rashi comments that “the tribes of Israel were exiled to the lands of the Canaanites all the way to Tzarfat, and the people of Judah were exiled to Sepharad”. In the Middle Ages, “Canaan” was used by Jews to refer to the lands of Eastern Europe, while “Tzarfat” (originally a town in what is today Lebanon) became associated with France (as Rashi himself says in this same comment). “Sephard” became associated with Spain, and gave rise to “Sephardic” Jewry. In other words, what Rashi is saying is that the Israelite tribes of the north were exiled to the lands where Ashkenazi Jews lived (from Eastern Europe to France), while Judah was exiled to Spain and became the Sephardic Jews!  Jewish community divisions in the Middle Ages Following the Muslim conquest of Spain in the 8th century, the Jewish population in the peninsula exploded. For a long time, Jews generally lived well and prospered. Unfortunately, the “Golden Age” of Sephardic Jewry in Spain ended sometime in the 12th century, and many started to leave (including the great Rambam, Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1138-1204, who ultimately settled in Egypt). By 1492, all Sephardic Jews were expelled. Many settled in Morrocco and other parts of North Africa, with large groups also settling in Italy, Greece, Turkey, and across the Mediterranean. I believe all of these communities that have roots in Sephard are best identified with the tribe of Yehudah. Closely related to the Sephardic Jews are Yemenite Jews. Although they are distinct geographically and genealogically, Yemenite Jews traditionally followed Sephardic halakhah, particularly as set forth by the Rambam, whom they held in the highest esteem. In his writings, the Rambam refers to himself as “Moshe the Sephardi” (see, for example, the introduction to his Mishneh Torah). We know the tribe closest to Yehudah was Binyamin, and Jerusalem was built across both territories. Thus, we can parallel Yemenites to the tribe of Binyamin—terms that are linguistically connected, too. “Yemen” literally means “south”, or yamin, meaning to the “right” when facing the rising sun to the east. “Binyamin” can literally be read as “son of Yemen”! Ephraim, Menashe, Dan Opposite Yehudah, the other dominant tribe in ancient Israel was Ephraim, from whom stemmed many of the kings of the north. We know Ephraim was exiled to the east of Israel, to what soon became the Persian Empire. Jews that lived across the Persian Empire did retain oral traditions that they are descendants of Ephraim—including some Iranian Jews, Afghan Jews, and my own Bukharian community. The Bukharian Jewish language is very similar to Farsi, as are many aspects of the culture and cuisine. This is also true of Kavkazi and “Mountain” Jews on the other side of the Persian Empire. Closely related geographically and historically, though culturally and linguistically distinct, are Georgian Jews. I believe this entire region of Jewish communities, under the umbrella of ancient Persia, can be strongly identified with the tribe of Ephraim. (My own family tree begins with a man named Pinchas who was born in Isfahan in Iran and migrated to Bukhara in the 1700s. His nickname was the Farsi palivan, a “hero” or “great warrior”, which later became “Palvanov” when Russified by the Russian authorities that conquered the region, hence my last name).

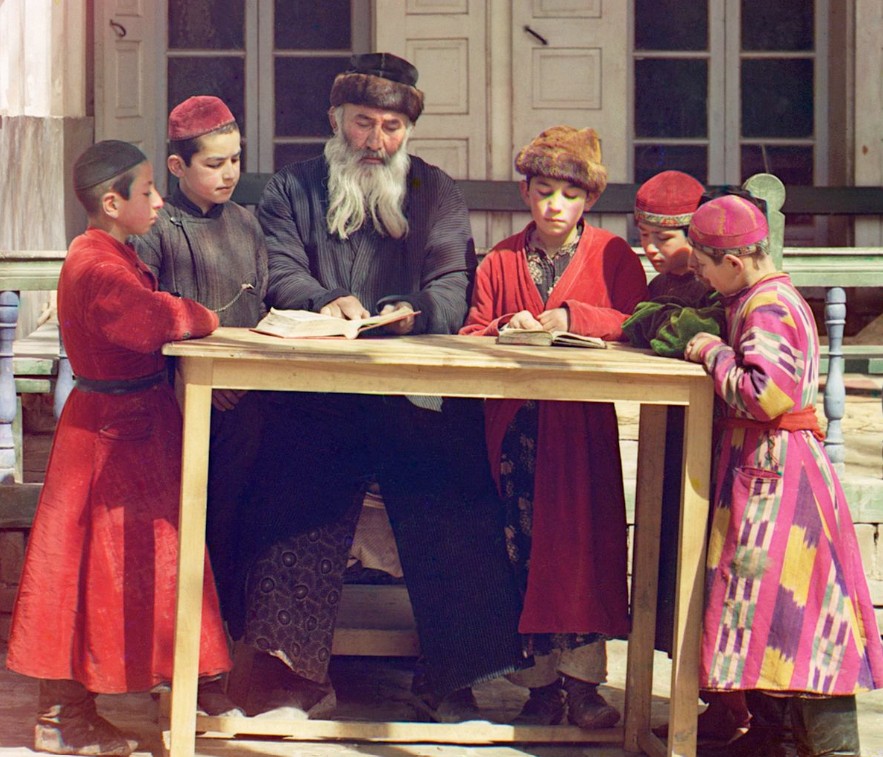

Bukharian Jews learning in Samarkand (in today's Uzbekistan), early 1900s Further to the east is another people that is very close to Iranian, Bukharian, and Afghan Jews: the non-Jewish Pashtuns of Afghanistan. It has long been said that the Pashtuns are one of the Lost Tribes of Israel. They retain many practices that hint to their Jewish and Israelite origins. They also carry very Biblical names, and many are part of the large “Yusufzai” clan, ie. children of Yosef. My good friend Rabbi Harry Rozenberg has been in contact with Pashtuns for years, and says many of them are well aware of the connection and some do hope to ally with Israel soon, when the geopolitics are more favourable. In recent years, Afghanistan has actually been in conflict with Iran as well, and tensions have spilled over into bloody clashes along the Helmand River. I believe that the Pashtuns are best paralleled to Ephraim’s older brother Menashe, whose name literally means “forgotten”. Yosef named Menashe based on the fact that he had forgotten his earlier troubles and even "forgot" his father’s house (see Genesis 41:51). In the same way, the Pashtuns have been “forgotten” and not considered Jewish or part of the House of Israel. Going further east, there are communities in northern India and Myanmar that call themselves “Bnei Menashe” and believe they are Lost Tribes. There have even been Lost Tribes communities in China and Japan. All of these might be put together with the Pashtuns and other Lost Tribes communities across Asia who have been “forgotten” (until now). Now, some might point out that many Pashtuns are associated with the Taliban and are not particularly friendly with Israel. I think this might be symbolized by the fact that the tribe of Menashe was territorially split in half, with one portion inside Israel and the other portion outside on the east side of the Jordan River. It might indicate that there are those within the house of Menashe that are currently not on the same side politically as Israel!  On the neighbouring continent of Africa can be found many Lost Tribes communities, too (such as the Igbo in Nigeria), in addition to the Abayudaya in Uganda who converted to Judaism in the last century and, of course, Ethiopian Jews. One tradition holds that Ethiopian Jews stem from the tribe of Dan. This is a fitting parallel, and can spiritually be traced to the mystical Sefirah of Gevurah, also called Din, or “judgement”, the same as Dan. In Jewish tradition, following the Great Flood, the known world was divided up between the three sons of Noah. Shem got Asia, Japheth got Europe, and Ham got Africa (ham literally means “hot”). Kabbalistically, Shem and Asia parallel the Sefirah of Tiferet, while Japheth and Europe correspond to Chessed, and Ham and Africa to Din (which might explain the very difficult history of Africa and the tragic subjugation that African peoples have experienced). With this blueprint in mind, we can see how African Jewish and Lost Tribes communities can be linked to the tribe of Dan. On the neighbouring continent of Africa can be found many Lost Tribes communities, too (such as the Igbo in Nigeria), in addition to the Abayudaya in Uganda who converted to Judaism in the last century and, of course, Ethiopian Jews. One tradition holds that Ethiopian Jews stem from the tribe of Dan. This is a fitting parallel, and can spiritually be traced to the mystical Sefirah of Gevurah, also called Din, or “judgement”, the same as Dan. In Jewish tradition, following the Great Flood, the known world was divided up between the three sons of Noah. Shem got Asia, Japheth got Europe, and Ham got Africa (ham literally means “hot”). Kabbalistically, Shem and Asia parallel the Sefirah of Tiferet, while Japheth and Europe correspond to Chessed, and Ham and Africa to Din (which might explain the very difficult history of Africa and the tragic subjugation that African peoples have experienced). With this blueprint in mind, we can see how African Jewish and Lost Tribes communities can be linked to the tribe of Dan.

Dan was often dismissed as the “lowliest” tribe, and was the last in the travel configuration during the forty years in the Wilderness following the Exodus. The Sages say that Dan was at the very back (see Rashi on Numbers 10:25), picking up lost objects, and also fending off attacks from Amalek. In selecting people to build the holy Mishkan, God deliberately chose one craftsman from the respected tribe of Yehudah (Betzalel), and one from the lowliest tribe of Dan (Oholiav) so that people would see there is no difference. All should be respected equally and held in the same high esteem. (Similarly, the Zohar says that Mashiach will have a key helper named Saryah, from the tribe of Dan, see for instance III, 194b) The symbolic nature of Dan having to travel at the back can be seen as a reference to black history and the injustice of having had to sit at the “back of the bus”. Reuven, Shimon, NaftaliWe now turn our attention to Europe and the Ashkenazi domain. Rashi told us that tribes from the northern kingdom of Israel were exiled to the lands between Eastern Europe and France. The firstborn of the northern tribes was Reuven. His father Jacob described him as the choicest of his fruit, "exceeding in rank and exceeding in boldness" (Genesis 49:3). Indeed, Ashkenazi Jews in recent centuries flourished, prospered, and took the lead in many fields of business, law, government, science, medicine, and technology. Whether in Germany or Lithuania, the Russian Empire or America, Ashkenazi Jews have "exceeded in rank" and pioneered boldly. That said, Reuven ultimately lost his firstborn status because he failed to take the leadership reigns when necessary. In that same deathbed blessing, Jacob went on to describe Reuven as fearful and impetuous, even bringing his father disgrace! (Genesis 49:4). Centuries later, the prophetess Deborah also criticizes the tribe of Reuven for not assisting Israel in battle (Judges 5:15-16). This jumped out at me as a possible reference to the Ultra-Orthodox or Haredi Ashkenazi world which has in recent years and months so opposed the IDF and military service. This community is full of talmidei chakhamim and rabbis that should be the “firstborn” and take the reigns of leadership, but are instead fearful and isolate themselves. They are often putting themselves on the “other side” of Israel, too, which may again be symbolized by Reuven settling on the east side of the Jordan River, opposite everyone else. (Interestingly, you find similar opposition on the other side of the religious spectrum, where Reform Jews who are also of Ashkenazi descent tend to be extremely critical of Israel and the IDF, too!) Closely related are the Hasidic Jewish communities, which I believe neatly parallel the second-born Shimon. We know that Shimon was actually not given specific tribal boundaries, and instead received a handful of towns in the Holy Land. Thus, central to the identities of ancient Simeonites was the specific town from which they hailed. The same is true for Hasidic communities, who are all labelled and identify based on their affiliated origin town, whether Satmer (Satu Mare in Romania), Bobov (in Poland), Belz or Vizhnitz (both now in Ukraine). These communities tend to be deeply isolationist, and have little contact with Jews outside of their kahal. That might be alluded to by Jacob’s deathbed words to Shimon saying that he is not part of their kahal! (Genesis 49:6) Meanwhile, Moses didn’t mention Shimon at all in his final blessing (Deuteronomy 33). There is no doubt that in the forthcoming Messianic Age, these communities will be re-integrated and reunited with their brethren.  Now, the above separation and isolationism of Hasidic groups clearly does not apply to Lubavitch (Chabad). Lubavitchers are well-known for their fantastic kiruv and outreach work. They interact with all communities, around the world. They do usually support IDF soldiers, and some will serve in the army themselves, or serve as chaplains, or other support staff. The same can be said of Breslov Hasidim, though certainly not to the same extent as Chabad. Then there is the Dati Leumi or “Religious Zionist” community, who make up a major part of the IDF, and also do a tremendous amount of outreach work all over the world (through organizations like Mizrachi and Bnei Akiva). Although generally not officially “Hasidic”, many from this community have a Hasidic-style rebbe in the great Rav Kook (1865-1935, pictured at right), who is central to their philosophy and worldview. In fact, today you find elements of Chabad, Breslov, and Rav Kook fusing together into a new group referred to as Habakkuk (the name of one of the Biblical prophets and a sefer in Tanakh). Thus, I believe these three groups are best paralleled to the fleet-footed tribe of Naftali, going all over the world to spread Torah and mitzvot. (It’s fun to point out that Naftali [נפתלי] is an anagram of tefillin [תפלין], symbolic of the Tefillin Campaign that helped make Chabad world-famous, and that has now become central to everyone’s kiruv work.) Now, the above separation and isolationism of Hasidic groups clearly does not apply to Lubavitch (Chabad). Lubavitchers are well-known for their fantastic kiruv and outreach work. They interact with all communities, around the world. They do usually support IDF soldiers, and some will serve in the army themselves, or serve as chaplains, or other support staff. The same can be said of Breslov Hasidim, though certainly not to the same extent as Chabad. Then there is the Dati Leumi or “Religious Zionist” community, who make up a major part of the IDF, and also do a tremendous amount of outreach work all over the world (through organizations like Mizrachi and Bnei Akiva). Although generally not officially “Hasidic”, many from this community have a Hasidic-style rebbe in the great Rav Kook (1865-1935, pictured at right), who is central to their philosophy and worldview. In fact, today you find elements of Chabad, Breslov, and Rav Kook fusing together into a new group referred to as Habakkuk (the name of one of the Biblical prophets and a sefer in Tanakh). Thus, I believe these three groups are best paralleled to the fleet-footed tribe of Naftali, going all over the world to spread Torah and mitzvot. (It’s fun to point out that Naftali [נפתלי] is an anagram of tefillin [תפלין], symbolic of the Tefillin Campaign that helped make Chabad world-famous, and that has now become central to everyone’s kiruv work.)

Issachar & Zevulun, Gad & Asher Coming back to the Middle East, we have the Mizrachi communities of Lebanese, Syrian, Kurdish, and Iraqi Jews. These fit nicely with the tribe of Issachar, which was known to be both wise and wealthy, both great Torah scholars and excellent merchants (see an in-depth analysis of Issachar and Zevulun here). Mizrachi Jewish communities did indeed produce great chakhamim like the Ben Ish Chai, as well as some of the wealthiest Jewish families and philanthropists, like the Sassoons and the Safras. Sharing these same lands are the Druze, who are not Jewish, and have their own religion centered around Jethro (father-in-law of Moses). In recent years, Druze leaders have suggested that they are Lost Tribes, too, and made the case that they come from the tribe of Zevulun (which I spoke about in this class). It is worth pointing out that many Druze have served valiantly in the IDF and in Israel’s border police. In turn, Israel has taken the lead in protecting Druze communities currently under attack and persecution in Syria. Many Druze have already integrated strongly into Israeli society, and it is quite likely that this trend will continue in the decades to come.

The Shrine of Jethro in Hittin, Northern Israel is a major holy site for the Druze

The last Jewish community left is the little-known Romaniote community. Their name comes from the old Eastern Roman Empire (or Byzantine Empire), which later fell to the Ottomans. Most of them lived in what is today Greece. Romaniotes are a distinct community with a distinct language (Yevanic). Romaniotes can be paralleled to the little-known tribe of Gad, of whom we have almost no information. Intriguingly, when Gad was born his mother Leah said bagad! We read it as if she said ba gad (בא גד), that “good fortune has come”, but the actual spelling in the Torah text is bagad (בגד), literally a “traitor”. I believe this might secretly allude to the most famous and infamous Romaniote Jew in history—the false messiah and traitor Shabbatai Tzvi, whose unfortunate impact on Jewish history is still felt to this day. This might be further alluded to by ancient Gad’s territorial location being, like Reuven and half of Menashe mentioned above, “outside” of Israel proper. Lastly, we have the tribe of Asher. The most famous “Asher” family in history are the Ben Ashers of the 10th century. They produced the definitive Tanakh text and what became the Aleppo Codex. Many have argued that the Ben Asher family were Karaite Jews. Recall that the Karaites were a community that emerged in the 9th century and rejected the Talmud and rabbinic tradition. Nonetheless, in the centuries that followed, Karaites did adopt some rabbinic practices, and many embraced Kabbalah and traditional mysticism. (Some even revered the Rambam and believed he was secretly a Karaite!) In turn, Karaite philosophy and Karaite Torah commentaries influenced rabbinic ones, including the writings of Ibn Ezra. Karaites have had an interesting status in halakhah. Some rabbinic authorities sought to detach the Karaites from the rest of Jewry, while others wanted to reintegrate them. In general, intermarriage with Karaites was forbidden. In 1971, Rav Ovadia Yosef ruled it permitted, and actually encouraged marriage with Karaites, hoping that this would bring Karaite communities back into the rabbinic Jewish fold. I believe Karaite Jews can be paralleled to the tribe of Asher. To summarize all of the above (in order of tribal birth):

Our only goal now is to unify all of the “tribes” of today into a singular people. We know that we need unity and ahavat hinam to bring about the Final Redemption. So let’s put aside our differences and remember that truly we are one people, all children of Israel. It’s certainly beautiful to have different cultural traditions, diets, and forms of expression, but we should never lose sight of the fact that we have one God and one Torah, and we should ideally have one halakhah and one hashkafa, too. It should be just like the inauguration of the Mishkan in parashat Nasso(Numbers 7), when the Torah describes the offerings and gifts that each tribe brought. Every single offering is exactly the same, yet the Torah repeats it verbatim twelve times. Why bother spending so many extra lines to repeat the same thing? The Torah is usually very concise and terse! The repetition is supposed to emphasize that, although each tribe is culturally different and may have different skin tones and appearance, they all served Hashem in the exact same way, and halakhically brought the exact same contributions. This should be our national goal, and what each and every one of us should work towards. Through this, we will merit to experience the Final Redemption speedily and in our days. Shabbat Shalom! |

No comments:

Post a Comment