How Many Parashot in the Torah?

This week’s parasha is Chukat, and this year it is read independently although it is often read together with the following parasha of Balak. Why is it that in some years we read certain parashot on their own, and in other years they are linked to another? The simple answer is because of the dynamic Jewish calendar. A typical Jewish year has 50 weeks, while a leap year has an extra month of Adar resulting in 54 weeks. The Jewish calendar cycle runs 19 years, and there are 7 leap years within a 19-year cycle that have 54 weeks. Naturally then, the Torah needs to be divided up into 54 parashot so that there is a parasha for each Shabbat in a leap year. (In times past, some communities, especially in Israel, actually read the Torah once over a span of about three years, not one year, splitting the parashot into smaller segments.)

Practically speaking, there will always be some Shabbats that fall in the middle of a holiday, including Pesach and Sukkot, and sometimes others like Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Plus, the final parasha of V’Zot haBerakhah is always read on Simchat Torah and not on its own Shabbat. So, in a typical year there are usually no more than 47 Shabbats with a parasha. That means you have to combine the remaining seven (of the 54 total) with another parasha.

When it comes to which parashot should be combined, there are differing traditions, especially among Yemenite and Syrian communities, but the general consensus today links the following seven pairs: Vayak’hel and Pekudei, Tazria and Metzora, Acharei and Kedoshim, Behar and Bechukotai, Chukat and Balak, Matot and Masei, Nitzavim and Vayelekh. Three of these pairs are linked because they are thematically similar, and the other four are linked simply because they are short and adjoining, making them easy to combine into one. (The latter is especially true for the two shortest parashot in the Torah, Nitzavim and Vayelekh with just 40 and 30 verses each, respectively.)

Which parashot are combined in which years also depends on the approaching holidays. For example, parashot are scheduled so that Bamidbar typically precedes Shavuot, while Nitzavim (with or without Vayelekh) typically precedes Rosh Hashanah. Of course, we must have the penultimate Ha’azinu before Sukkot so that the final V’Zot haBerakhah is left for Simchat Torah, and the first Beresheet for the first Shabbat of the year following the holidays.

To summarize, we have a maximum total of 54 parashot, but up to seven can be combined with others, depending on the type of year, to leave us with 47 parashot. But then, amazingly, the Zohar comes in and says the Torah actually has 50 parashot!

50 Parashot, 50 Gates

When Hashem revealed to Abraham that he was about to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah, Abraham famously challenged it, saying: “Perhaps there are fifty righteous people in the city?” (Genesis 18:24) The Zohar adds that what Abraham was really saying is: “Maybe there are those who learned all fifty parashot of the Torah?” and therefore do not deserve to be exterminated. The Zohar itself then questions this statement, saying that the Torah doesn’t have fifty parashot, but fifty-three. Some do not count V’Zot haBerakhah since it is not read on its own Shabbat, but only on Simchat Torah. Others don’t count Vayechi, to be explained below. Some say the notion of 53 parashot is alluded to by the word gan (גן), “garden”, which has a value of 53. When King Solomon describes going into “the Garden” multiple times in Shir haShirim, it mystically alludes to plunging into the depths of Torah.

The Zohar concludes by saying that each of the five books of the Torah contains the Ten Commandments in it (in some way), meaning that altogether there are 50. It’s not clear what this means. Does each parasha in each of the books correspond to one of the Ten Commandments? Should we, then, expect ten parashot per book? To have a total of 50 parashot makes a lot of sense, since the Zohar also speaks of Nun Sha’arei Binah, 50 Gates of Understanding.

These fifty correspond to the fifty-year cycle of the Jubilee. If the final parasha of the Torah, V’Zot haBerakhah, corresponds of the fiftieth gate, it works really neatly because the fiftieth gate is associated with overcoming death and attaining ultimate truth, which Moshe did at his own passing described in that parasha. He died on Mt. Nebo, which our Sages explained was nun-bo, alluding to Nun Sha’arei Binah. So, can we break down the Torah into 50 parashot as the Zohar suggests, ten per book? We find in our Chumash that Beresheet has 12 parashot, Shemot has 11, Vayikra and Bamidbar have 10, and Devarim has 11. But if we look a little closer, the Zohar’s suggestion might work out after all:

The books of Shemot and Bamidbar already have ten parashot each. Devarim has eleven, but we typically link the super-short Nitzavim and Vayelekh into one anyway, giving us a total of ten, too. Shemot has 11 parashot, but we similarly link Vayak’hel and Pekudei, leaving us with ten. What about the 12 of Beresheet?

Interestingly, the final parasha of Vayechi actually does not have its own start in a proper Torah scroll. It continues literally mid-sentence from the previous parasha of Vayigash! The implication is that they are not separate at all, and can be read as one parasha. In fact, the precise halakhic definition of a parasha is a continuous chunk of Torah without breaks. The end of a parasha is delineated with a break of some sort, whether an “open” one indicated by a pei, or a “closed” one indicated by a samekh. There is no break at all between Vayigash and Vayechi, implying they make up one parasha. (Unlike all other parashot, there isn’t even a Masoretic note at the end of Vayigash to specify the number of verses!) This would explain the alternate opinion that the Torah has 53 parashot, since this is the actual number of breaks in the Torah.

If we go one step further, we find that Vayigash is also linked directly to the previous parasha of Miketz. In fact, Miketz seems to end abruptly while Joseph is still speaking, and then Vayigash begins with Judah’s response to Joseph. This is the only time in all of Sefer Beresheet where two parashot are linked so directly, without any concluding statement or introductory verse between them, literally in the middle of a conversation. One can thus read the entire narrative from Miketz to Vayechi continuously as one, split in three for convenience.*

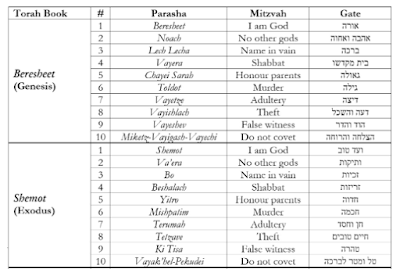

With that, we can neatly take the Zohar’s suggestion and create a 50-parasha framework for the Torah, corresponding to the Ten Commandments (times 5) and the 50 Gates of Understanding**. As you look at the connections between the columns, you will surely find how neatly and perfectly they all fit together:

To illustrate with just a few examples: We can see how the first parasha of Beresheet beautifully ties to the first mitzvah of knowing God and the first gate of light (which began Creation). Lech Lecha is where God first reveals His name to Abraham and gives him 100 blessings (the value of לך לך, see Zohar I, 76b, Sitrei Torah), so it naturally links to the mitzvah of not taking God’s name in vain and the gate of blessing! Toldot is where Esau resolves to murder Jacob, so the corresponding mitzvah is not to murder, while Vayeshev contains multiple instances of false reports so the corresponding mitzvah is not to bear false witness! Go through the rest of the parashot and you will see many more incredible and striking connections.

Shabbat Shalom!

***********************

*A fun note to point out: As I’ve mentioned multiple times over the past couple of years, Miketz is the only parasha where the Masoretic note doesn’t just say the number of verses, but also the number of words. The number of words happens to be 2025, which I’ve argued alludes to our current year. Meanwhile, the Masoretic note on Vayechi states that it has 85 verses, and we are currently in the Hebrew year 5785!

**To go into the 50 Gates is far beyond the scope of this essay. There are different lists identifying the 50 Gates, and how they are intertwined with the Sefirot, including the popular 7 x 7 array of the lower Sefirot, plus Binah; and the Ramak’s array of 10 x 5 (which would fit this chart more naturally). Here, I elected to go with the list of fifty gates as they appear in many siddurim and machzorim, including the “Great Kaddish” of the High Holidays and in many Havdalah prayers. (For a very long time, I’ve been working on a sefer to explain the 50 Gates and link all of the fifties together, but it likely won’t be ready for several more years.)

www.MayimAchronim.com

No comments:

Post a Comment